Birds of A Feather: Lorenzo Revisited

Sabtu, 18 Agustus 2012

0

komentar

A WALLPAPER CASE STUDY BY ROBERT M. KELLY

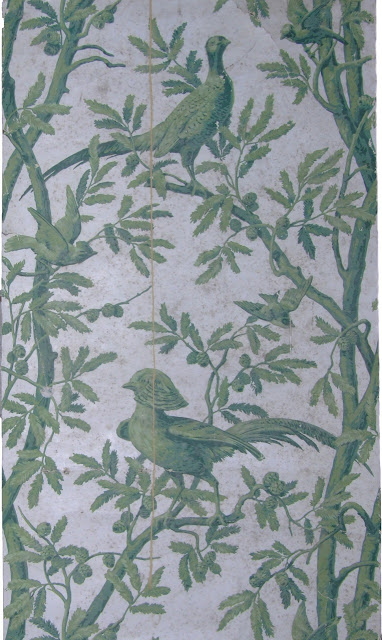

A while ago the Wallpaper History Review carried a query about a wallpaper which graced the Library, one of two state rooms either side of an impressive entrance hall at Poltimore House, near Exeter, Devon. The Friends of Poltimore House sought information about this “. . . design of oriental-type green pheasants on a white ground . . . when the paper was taken down [in 1945] the names of the paperhangers and a date in the 1880s were discovered but nothing further is known of its origin or date of manufacture. It is a hand block-printed paper, 660mm (25.75 inches) wide with a repeat pattern of 1074mm (42.5 inches).”

|

| 1. green document extant at Poltimore House |

|

| 2. Library at Poltimore House about 1912 |

|

| 3. Lorenzo, built 1807 |

Lorenzo arose at a time when the Holland Land Company, of which Lincklaen was an agent, owned as many as three million acres in far western New York and Pennsylvania. But, it was a time of boom or bust. As the market sputtered, the Company more or less unloaded thousands of acres on Lincklaen. The builder of Lorenzo died penniless in 1822. Oliver Phelps of Suffield, Connecticut owned over two million acres in mid-New York State adjacent and to the east of the Holland Purchase, but he died broke too, in Canandaigua. Phelps’ claim to wallpaper fame is the glorious suite of Reveillon wallpapers which were installed during an enlargement of his house in 1795. Phelps lost the house in 1802, but all was preserved by the Hatheways, who began their long residency in 1811.

Lorenzo’s next owner was Lincklaen’s brother-in-law, Jonathan Ledyard. The house then passed to Jonathan’s son, Lincklaen Ledyard, in 1843. His aunt asked him to preserve the family name, so he reversed his name. From then on, he was Ledyard Lincklaen. Lorenzo became the family's summer respite from their professional and social careers in Albany (the capital of New York) and New York City. Ledyard Lincklaen’s daughter married Charles S. Fairchild in 1871, and the couple inherited Lorenzo in 1894. Fairchild was Attorney General of New York; he prosecuted the Tweed Ring and the Canal Ring, and later became Secretary of the Treasury under Grover Cleveland. It was during the Fairchild residency that the block-printed bird paper was installed in the central hall around 1901.

On my first visit to the house in the fall of 1991 I was shown end rolls with “Zuber # 6872 SPRS” printed on the selvedge. These had been squirreled away in the attic. Condition of the hallway installation was poor; the paper had been printed on highly acidic paper and hung directly on plaster walls. Moisture had migrated into the paper stock, saturating and damaging the paper and distemper ground. Some areas of the wallpaper were lighter than others; this proved to be where it had pulled away from the wall. It was decided that conservation was not feasible. This difficult decision was made more palatable by the discovery that, against all odds, Zuber still had the blocks! Plans for the installation of a reproduction wallpaper moved ahead and the walls were stripped. After plaster repairs the walls were sized with traditional glue.

|

| 4. Barry Blanchard trimming selvedge |

Mrs. Fairchild donated samples of the bird paper to the fledgling Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in 1900 (at that time the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration), along with samples of a Reveillon arabesque (IVB9, manufacture Reveillon no. 688, dated 1789 in Bernard Jacqué's catalogue raisonnè). The arabesque came from a different house on the Lorenzo estate. I shall never forget the discovery of a harp tax stamp on the exceedingly rough canvas which supported the paper. It did my Irish-American heart good. Both canvas and paper had been stretched and tacked to a folding screen.

While researching this project, we soon discovered that a nearly identical design shows up in an early 20th century portfolio of samples from A. L. Diament; the ad states that the paper is “Machine Printed by . . . Desfosee & Karth . . .”, and that “ . . . a 52 inch, hand blocked linen exactly matches the paper.”

|

| 5. page from an A. L. Diament portfolio |

One avenue to explore, which consumed most of 1992, was having an American finishing company treat the wallpaper after production. Another strike-off on the distemper ground was forwarded to finishing companies. Though improved, the treated paper still fell short by a wide margin. It was not possible to add sheen to the ground without at the same time robbing the design colors of their flat finish. And, the hand-brushed ground still had a rough quality totally lacking in the original. After several more exchanges, Zuber agreed to strike off the design on a ground supplied by a third party, with a view to printing the entire run on a contract ground. With this encouraging news the search was on.

Guy Evans, reproduction fabric supplier, responded that a distemper ground could be made and polished in England, but the width was a sticking point—the rails and tables to accommodate the 25.75” width were no longer used. Norman Gibbon, manager for Sanderson, confirmed this and said that Sanderson did not use polished grounds. Their printers insisted that a relatively soft ground was needed to take the distemper colors.

Bernard Jacqué at the Musée du Papier Peint wrote back that in France, too, the polishing process had been abandoned. However, he pointed in a new direction. He told us that in East Germany, they were still using turn-of-the-century factory methods. He supplied the name of a West German wallpaper consultant, Lutz J. Walter of Stuttgart. My German is not perfect, and Walter’s English was not much better. Despite this, we were soon faxing and phoning. He'd already supplied custom blockprints on polished grounds for the restoration of Friedrich Schiller's house in Weimar, and forwarded samples to be tested by New York State conservations labs. The weight and texture were acceptable, and if the coating could be increased and smoothed a bit more, we would be in business.

But, Walter reported that German grounds are only 22 inches wide. Back to Jacqué. After some negotiation a French ground was located in the correct width. A test piece was sent for polishing to East Germany and forwarded to Zuber. A strike-off was sent stateside for examination and test hanging. The strike-off was a success. Next: a small disaster. The first 1000 meters had been polished wrongly; they were shaded! It's a credit to Walter’s professionalism that the printing was halted; he went back to square one. The next shipment was satisfactory and was sent to Zuber, arriving safely in May, 1994. By the end of the year it was at the house, ready for hanging.

6. newly papered hallway, 1995 |

You would think that that would be the end of the story. Yet, oddly enough, I kept running into this pattern. Now hold onto your hats, the journey gets a little dicey ahead. It even includes a wartime escape by an international man of mystery! Below is yet another iteration of the design, this one from around 1918:

|

| 7. Plate XXVI, Pheasant and Larch from“Decorative Textiles...”, Hunter. |

“Today in the United States, on account of labour conditions, the block printing of textiles is impracticable. Nevertheless, we have block prints (Plates XXVI and XXVII) in both new and old designs, which, though printed in England, were originated in New York by Harry Wearne, head of the ancient Zuber works at Rixheim in the heart of the war zone, from which Mr. Wearne, who is an English citizen, escaped into Switzerland just as the British ultimatum to Germany expired. Mr. Wearne, whose American connexions have been close for many years, and who has passed much of his time here, has now taken up his residence permanently in the United States and may now be able here to exercise as important an influence as Morris did in England during the later nineteenth century.”

So there you have it. Although it's certainly stretching a point to give the design an American provenance, it's clearly more than just a wallpaper design (a point previously made in the Diament advertisement). This brings up some interesting questions: Which came first, the A and B wallpaper widths, each 25.75”, or the full 52” or so linen version? How far back do these versions go? Who designed this thing, anyway?

Happily, there is a resolution.

Following our voluminous correspondence about the wallpaper versions, Jocelyn Hemming wrote to Philippe Fabry, curator at the Musée du Papier Peint, asking if he could help. He could. After consulting the Zuber archives, he responded as follows:

Dear Madam,

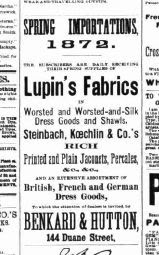

The Zuber wallpaper n° 6872 is a block printed wallpaper of the collection 1871-1872.

Le livre de gravure donne les indications suivantes :

"Cret(onne) Steinb(ach) K(oechlin) Mélèze & faisans

2 hauteurs sur 25 pouces – 4 m(ains) 8 planches

Dessin d'E(ugène) Ehrm(ann)

It’s a great thing after all this time to make the connection with the well-known designer Ehrmann, whose work appears in El Dorado. Don’t forget, the hooded pheasant from "Larch and Pheasants" also appears in El Dorado. By the way, Ehrmann’s initials, too, appear in that scenic, along with those of his co-designers Fuchs and Zipélius on some nearby stonework (but reversed; if you hold a mirror next to the wallpaper, the initials magically appear). It seems beyond question that with that maneuver the French crossed a line of some sort!

|

| 8. ad for Steinbach, Koechlin and Co. |

If Harry Wearne did have blocks carved for a fabric version in the early 20th century, it seems that his effort must count as a revival. So ends the tale of our birds of a feather. They certainly covered a lot of ground!

|

| 9. The hallway at Lorenzo |

_____

Some of this article is based on a special issue of Wallpaper Reproduction News, V. 6, No. 4 (Oct. 1995); Barbara Bartlett should be applauded for her continued stewardship of the house. Thanks are due Barry Blanchard and James Yates for helping me during the installation, and to Bernard Jacqué for his assistance in finding materials and technology for the reproduction.

To Poltimore House: much success!

For a map of the two large land tracts in New York (Holland Purchase and Gorham-Phelps Purchase), see this link:

File:WNY5.PNG

Lutz J. Walter is still making reproduction wallpapers in Germany:

www.historische-papiertapeten.de

Photo Credits: 1. green document extant at Poltimore Houe: courtesy of Ricky Apps, Friends of Poltimore House; 2. Library at Poltimore House about 1912: courtesy of Poltimore House Trust; 3. Lorenzo, built 1807: courtesy of WallpaperScholar.Com; 4. Barry Blanchard trimming selvedge: courtesy of WallpaperScholar.Com; 5. page from an A. L. Diament & Co. portfolio: private collection; 6. newly papered hallway: courtesy of WallpaperScholar.Com; 7. Plate XXVI, Pheasant and Larch from “Decorative Textiles,” Hunter, pg. 349; 8. ad for Steinbach, Koechlin, and Co.: New York Post, March 6, 1872; 9. the hallway at Lorenzo: courtesy Walter Colley.

TERIMA KASIH ATAS KUNJUNGAN SAUDARA

Judul: Birds of A Feather: Lorenzo Revisited

Ditulis oleh csdferwEHRTJR

Rating Blog 5 dari 5

Semoga artikel ini bermanfaat bagi saudara. Jika ingin mengutip, baik itu sebagian atau keseluruhan dari isi artikel ini harap menyertakan link dofollow ke https://wallpaper-emo.blogspot.com/2012/08/birds-of-feather-lorenzo-revisited.html. Terima kasih sudah singgah membaca artikel ini.Ditulis oleh csdferwEHRTJR

Rating Blog 5 dari 5

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar